Why Steve Quit the Mantle, Not the Mission

Captain America is often treated like the government’s superhero, but the comics have gone out of their way to argue the opposite. Steve Rogers is loyal to a set of ideals first, and he gets suspicious the second those ideals are used as branding for power.

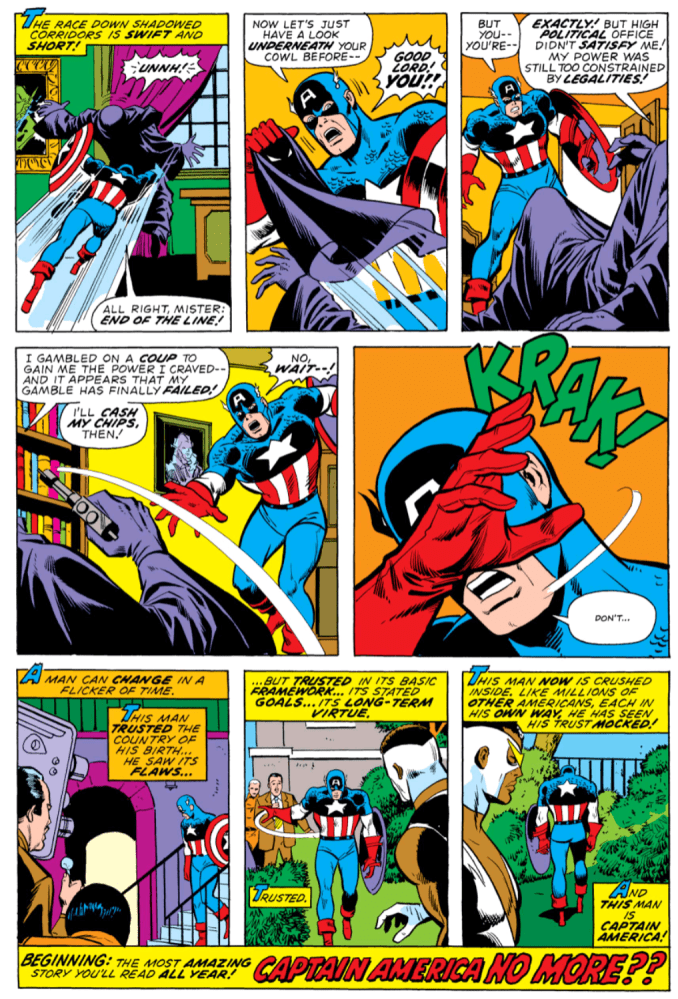

That tension explodes in the mid-1970s “Secret Empire” storyline, written by Steve Englehart. Steve and Sam Wilson uncover a conspiracy that isn’t just supervillain chaos. It’s corruption threaded through institutions, aimed at discrediting Captain America and reshaping public opinion. The story builds to a gut punch: Steve chases the conspiracy’s leader into the White House, and the reveal strongly implies the person at the top of the conspiracy is the President. The leader dies by suicide, and Steve is left with the kind of disillusionment you can’t punch your way out of.

So Steve does something that feels unthinkable for the character. He quits being Captain America.

He does not quit being Steve Rogers. He does not quit trying to protect people. He quits the symbol because he realizes the costume can be mistaken for an endorsement. If Captain America is seen as “the flag’s guy,” then government leaders can hide behind him, borrow his moral authority, and pretend their decisions are automatically patriotic.

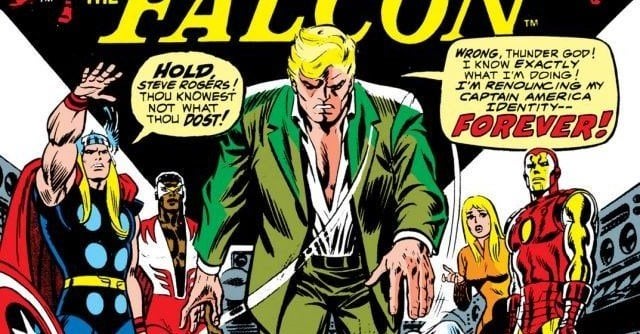

That’s where Nomad comes in. In Captain America #180 (December 1974), Steve takes on a new identity, Nomad, literally “the man without a country.” The point isn’t that he hates America. It’s that he refuses to let the government define what America means. Nomad is Steve trying to keep the mission while rejecting the idea that the state owns the symbol.

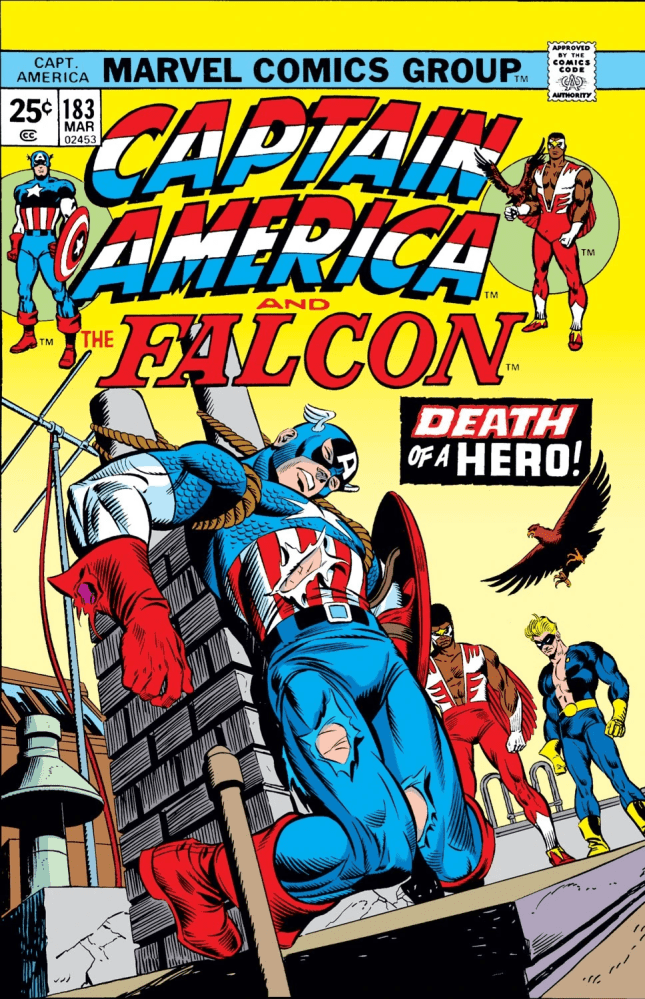

That experiment doesn’t last long, and the comics make sure you understand why. When Steve steps away from the shield, someone else tries to fill the gap, and the consequences are brutal. Roscoe Simons, inspired by the idea of Captain America, takes up the role and is murdered by the Red Skull. That death snaps Steve back into focus. He realizes the symbol is bigger than his personal crisis, and leaving it unattended creates a vacuum that either gets exploited or gets good people hurt.

So he comes back as Captain America, not because the government earned him back, but because the ideals are still worth defending, and the symbol still matters to the public.

That is the real takeaway of the Nomad era, and it’s why it keeps getting referenced whenever Captain America stories want to say something real. America’s ideals and America’s government are not the same thing. Patriotism is not obedience. If you care about the symbol, you don’t surrender it to power. You fight over what it means.

That idea lands differently when you look at the present and the reality of immigration enforcement raids.

When Enforcement Becomes Fear: ICE Raids Today

On January 7, 2026, an ICE officer fatally shot Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis during an ICE operation. Federal officials claim the shooting was self-defense, saying she tried to run over officers. Family members, local officials, and video of the incident dispute that. The city and nation demand answers and accountability. The details will be investigated, argued over, and litigated, but the broader impact is already plain: raids turn “policy” into something physical, frightening, and immediate for the people living through them.

This is where the Captain America question shows up in real life, and it’s uncomfortable on purpose. A government can claim it’s acting lawfully and still behave in ways that betray American ideals, especially when force is used, and the public is told to accept the official story first and ask questions later. At the same time, it’s easy for people to collapse the whole debate into teams and slogans.

The Nomad story refuses that simplification. It insists on the separation. You can believe in the country’s ideals and still challenge what the government is doing in the country’s name. You can treat accountability, restraint, and due process as patriotic expectations rather than partisan complaints. And you can defend national symbols without letting them become shields for harm.

That’s what Steve Rogers is trying to do when he stops being Captain America for a moment, then chooses to return. He is not protecting the government’s image. He is protecting the public’s claim to the ideals behind the image. If those ideals mean anything, they have to apply when it’s inconvenient, when people are scared, and when the machinery of the state is moving fast.

Captain America’s lesson is simple: the flag isn’t something the government gets to own; it’s something the people have to earn and protect by holding power to the ideals it claims to represent.

Leave a comment