Yellowstone is a big, messy, addictive modern Western that plays like a family tragedy dressed up in cowboy gear. Over five seasons it followed the Duttons, owners of the largest ranch in Montana, as they fought developers, politicians, corporations, and the Broken Rock Reservation to keep their land. It’s a soap opera with a saddle, and when it’s on, it’s really on.

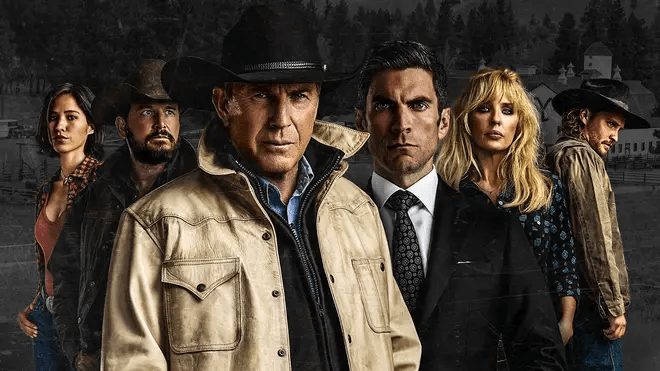

What makes the series work is the sense of scale paired with intimacy. One minute you’re getting those sweeping Montana landscapes and bone-crunching action beats, the next you’re locked in a kitchen argument that feels like it could tear the whole family apart. The cast is a huge part of that. Kevin Costner’s John Dutton is all granite authority and quiet panic, Kelly Reilly’s Beth is a live wire who can turn grief into a flamethrower, and the rest of the core players fill out a family that feels both mythic and painfully believable. Sheridan’s writing can be blunt, even melodramatic, but it’s also confident about what kind of show this is: high-stakes, morally muddy, and willing to let characters be ugly.

It’s not flawless. Yellowstone sometimes spins its wheels, repeats conflicts, or falls in love with its own tough-guy speeches. Later seasons got uneven, with storylines that drift or detour, and the final run had to pivot hard after Costner’s exit. Some critics thought the finale was clunky or overstuffed, while others felt it landed the emotional themes even if the road there was bumpy. Either way, the show rarely feels small, and even when it stumbles, it’s still compelling TV.

Where Yellowstone really sticks is in how it treats family ties. The Duttons aren’t just a family, they’re a fortress under siege. Love in this world is inseparable from protection, and protection is inseparable from control. John Dutton genuinely loves his kids, but he loves the ranch more, and he raises them to treat that inheritance like a holy war. The result is a family that’s loyal to the point of self-destruction.

Beth and Jamie are the clearest example. Their relationship is what happens when childhood wounds never heal and power becomes the only language left. It’s not sibling rivalry, it’s a decades-long argument about who “belongs” in the family and what loyalty costs. Kayce sits on the other side of that spectrum. He loves his father and his siblings, but he also wants a life that isn’t defined by trauma and debt to the ranch. His storyline is basically the question, “Can you stay tied to your family without letting it swallow your own?”

Then there’s Rip and the ranch hands, which shows another truth the series keeps circling: family isn’t only blood. Rip is chosen family, built through survival, work, and shared scars. The “brand” on the ranch is a brutal symbol, but it’s also the show’s way of saying that belonging can be forged, not inherited. By the end, the Dutton legacy is less about winning and more about what you’re willing to release so the next generation can breathe. The ranch is treated like a family member too, something loved fiercely, defended irrationally, and finally, in a way, let go.

So what does Yellowstone say about family ties? Mostly that they’re powerful, complicated, and dangerous when they become your whole identity. The show doesn’t romanticize loyalty as automatically noble. It shows how devotion can turn into possession, how legacy can become a cage, and how old pain gets passed down like property. At the same time, it argues that family is worth fighting for when the fight is rooted in care instead of ego. The healthiest moments in Yellowstone come when characters choose people over pride, and peace over “winning.” In a series where everyone thinks survival means holding tighter, the real growth comes from the few who learn when to loosen their grip.

Leave a comment